As Shelter Wait Times Soar, Older Homeless in Limbo Daily

June 28, 2017

By Sara Bloomberg

(Infographics by Sara Bloomberg and Reid Brown)

A 97-year-old, 3 people in their 80s waited weeks for beds

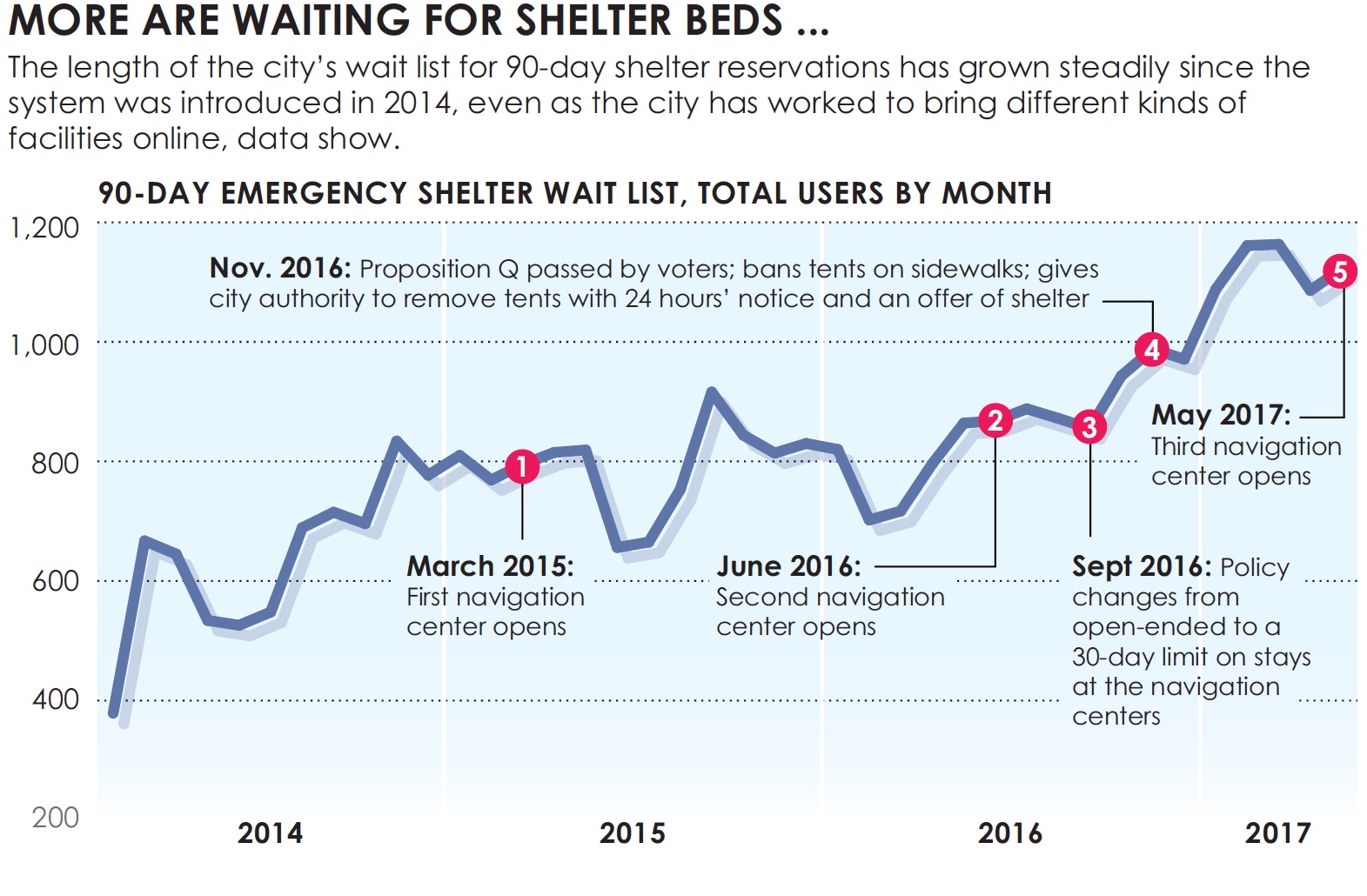

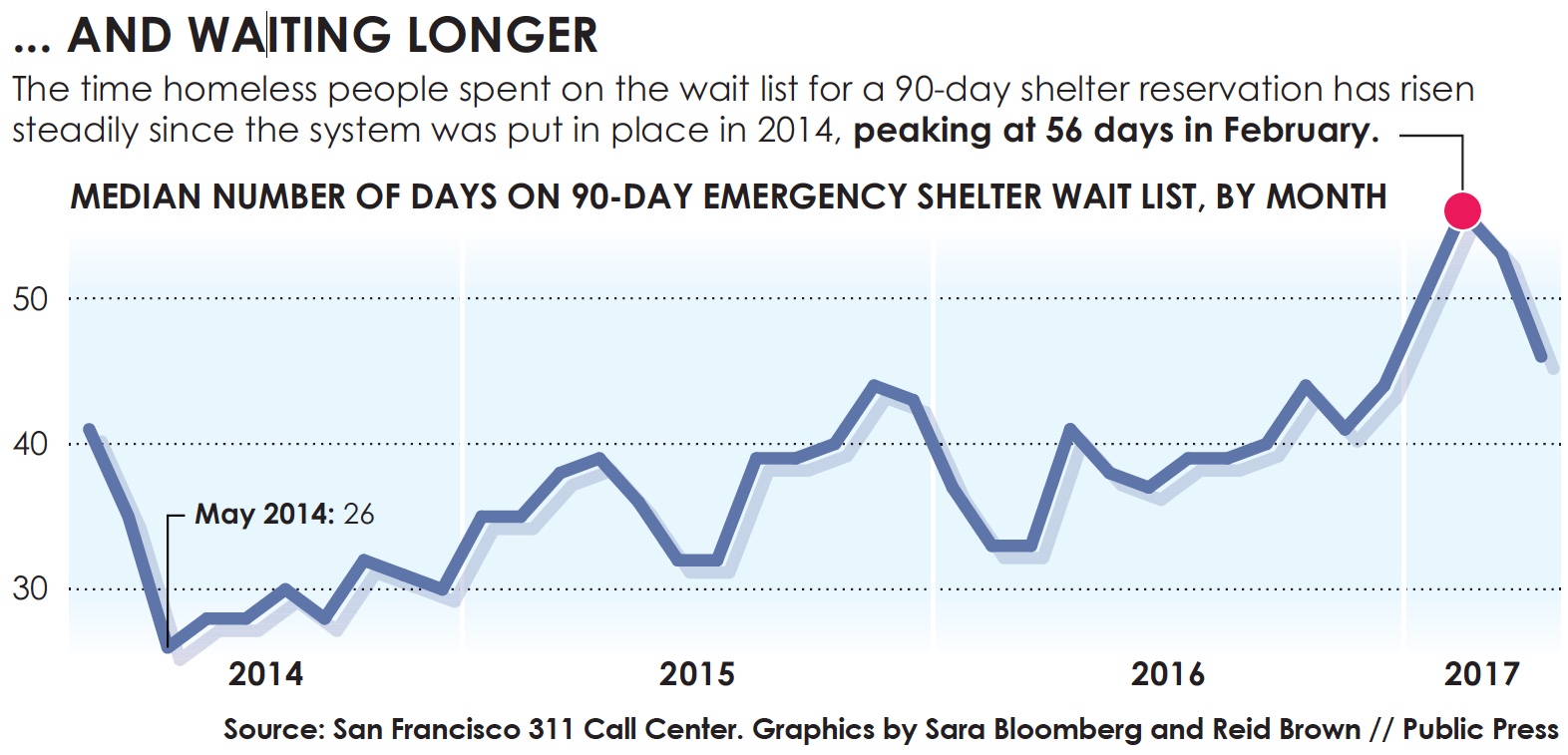

For thousands of San Francisco homeless people, the city’s emergency shelter wait list has provided a temporary reprieve from living on the streets. But the wait time for a bed has hit a record high, as growing demand outstrips availability, city records show.

The monthly median wait time for a 90-day bed increased from 26 days in early 2014, when the city began posting data online, to a peak of 56 in February 2017. By April, it eased to 46 days.

Among those waiting weeks on the list recently were a 97-year-old and three people in their 80s. They were just a few of the record number of homeless people seeking a bed on a list that has become a fixture in the lives of many.

The increasing wait for a shelter bed comes despite a relatively constant homeless population during the same period. The just-released 2017 biennial count came to 7,499, about the same as two years ago.

A top city official said several factors may be responsible for the growing wait list. Sam Dodge, deputy director of the city Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing, said he suspected that not everyone on the list was unhoused. He said people repeatedly use the wait list for a complex set of reasons.

“Sometimes it appears that people are making something work — either living with a family member or they found a temporary arrangement, whether an SRO [single resident occupancy] or other housing, and they’re nervous that it will disappear,” Dodge said in an interview. “So the reservation is a backup plan.”

But the increasing backlog coincides with changes at the Mission Navigation Center, which the city opened in March 2015 as an entry point to guide people from the street to permanent housing. When the city reduced open-ended stays to 30 days in September 2016, staff referred some people to temporary shelter. (The 30-day limit has since been increased to 60 days.)

The next month, the number of people on the shelter wait list jumped. It then fluctuated, before rising to its March peak of 1,163.

Data from the city’s 311 call center show that half of the people who manage to get 90-day stays reapply multiple times because they are still homeless.

Multiple 90-Day Stays

Thirty-seven percent have registered two to five times, while 8 percent have joined six to 19 times over the same period. A handful have used the wait list 20 times or more. One person has signed up 24 times.

The list, managed by the 311 call center and updated twice a day, is anonymous, publicly listing individuals by date of birth and a confidential identification number. A person listed must call within 10 days of getting picked or lose his or her place. If the person provided a phone number, the city texts or attempts to call. Otherwise, the only way to check one’s place is to call 311, access the list online or view updated bed availability at “various locations,” the instructions state.

Privacy rules prevent identification of people receiving shelter, and the Public Press could not track down individuals for interviews.

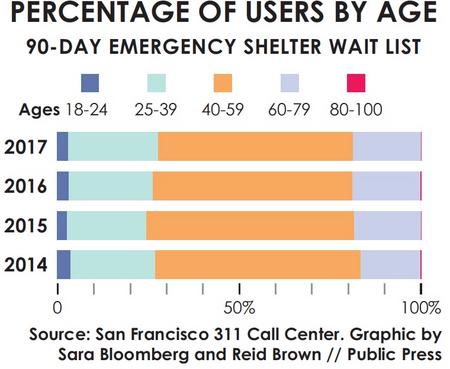

Of the people who signed up in May, about 30 percent were in their 50s, 15 percent were in their 60s and 3 percent were in their 70s.

City records show that the now-97-year-old has, since 2014, entered the wait list twice a year.

In early May, that person was No. 794 on a list of more than 1,130 names. Two weeks later, No. 473. By June 4, the person’s birthday, he or she was at No. 251. The reservation expired June 9, but the city confirmed that this person received a bed.

Although the wait list is technically first-come, first-served, the city does allot a handful of shelter beds for people who are considered vulnerable, including seniors.

“We do have some carve-outs within our shelter system for elderly and veterans, and people who are referred from the Homeless Outreach Team,” Dodge said. “We want to be fair and equitable, but it’s an important practical reality.”

At the same time, someone listed as 87 years old was at position 989. Without referrals from the outreach team, people have to chance it, and hope to claim spots in time.

Wait list policy also bars people from signing up for another spot until the last day of their reservations, preventing double-dipping but also forcing people to find other arrangements or live on the streets between stays.

“We would rather people get on the list when they still have shelter,” said Jennifer Friedenbach, executive director of the Coalition on Homelessness.

Despite its problems, the 311 system is a vast improvement on the old process, when there was no centralized list and daily lotteries were drawn at each shelter.

“We fought for the 311 system,” Friedenbach said. “We tried to make it easier for people.”

The bigger challenge now, she said, is knowing how many beds are being set aside and how many are left for those who are on the wait list.

Wait List Adds to Stress

For some homeless people, the wait list adds to the already significant stresses of life on the streets.

Lynn Mahr, 57, has stayed in at least three shelters over the past three years. Her most recent stay, in May, lasted only four days.

She said some of the other women were cliquey and mean, and called her names. The rules were restrictive. It was stressful.

But life outdoors offers its own traumas. She said a man raped her in May at Ocean Beach. Though he was caught by good Samaritans, she said she feared he would be released from jail soon.

Even if she wanted to stay in a shelter, the wait-list process is unforgiving.

“You’re at number 1,000, and then once you’re up you only have 10 days,” Mahr said. “I didn’t know I came up and missed it by a few days.”

Mahr has lived in San Francisco since 2006 but lost her housing and the Section 8 voucher that helped pay for it. City records show that she had a room in an Ingleside home until early 2015, when she lost an appeal involving a dispute with the landlord. As of early June, Mahr still had no shelter.

City officials recognize that the root of the problem is the lack of affordable city-funded housing for the destitute. Unless more short-term beds or permanent housing units open up, homeless people over 50 will continue to grow old on the streets.

“The baby-boomer cohort has always been over-represented, and they’re aging,” Dodge said.